Page 27 - John Barber's Oakham Castle and its archaeology

P. 27

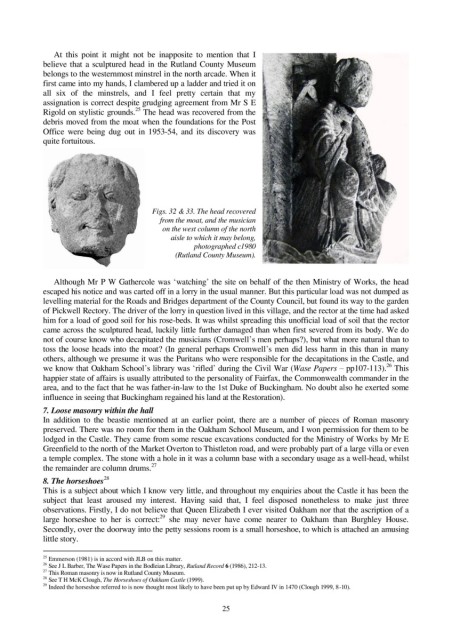

At this point it might not be inapposite to mention that I

believe that a sculptured head in the Rutland County Museum

belongs to the westernmost minstrel in the north arcade. When it

first came into my hands, I clambered up a ladder and tried it on

all six of the minstrels, and I feel pretty certain that my

assignation is correct despite grudging agreement from Mr S E

25

Rigold on stylistic grounds. The head was recovered from the

debris moved from the moat when the foundations for the Post

Office were being dug out in 1953-54, and its discovery was

quite fortuitous.

Figs. 32 & 33. The head recovered

from the moat, and the musician

on the west column of the north

aisle to which it may belong,

photographed c1980

(Rutland County Museum).

Although Mr P W Gathercole was ‘watching’ the site on behalf of the then Ministry of Works, the head

escaped his notice and was carted off in a lorry in the usual manner. But this particular load was not dumped as

levelling material for the Roads and Bridges department of the County Council, but found its way to the garden

of Pickwell Rectory. The driver of the lorry in question lived in this village, and the rector at the time had asked

him for a load of good soil for his rose-beds. It was whilst spreading this unofficial load of soil that the rector

came across the sculptured head, luckily little further damaged than when first severed from its body. We do

not of course know who decapitated the musicians (Cromwell’s men perhaps?), but what more natural than to

toss the loose heads into the moat? (In general perhaps Cromwell’s men did less harm in this than in many

others, although we presume it was the Puritans who were responsible for the decapitations in the Castle, and

26

we know that Oakham School’s library was ‘rifled’ during the Civil War (Wase Papers – pp107-113). This

happier state of affairs is usually attributed to the personality of Fairfax, the Commonwealth commander in the

area, and to the fact that he was father-in-law to the 1st Duke of Buckingham. No doubt also he exerted some

influence in seeing that Buckingham regained his land at the Restoration).

7. Loose masonry within the hall

In addition to the beastie mentioned at an earlier point, there are a number of pieces of Roman masonry

preserved. There was no room for them in the Oakham School Museum, and I won permission for them to be

lodged in the Castle. They came from some rescue excavations conducted for the Ministry of Works by Mr E

Greenfield to the north of the Market Overton to Thistleton road, and were probably part of a large villa or even

a temple complex. The stone with a hole in it was a column base with a secondary usage as a well-head, whilst

27

the remainder are column drums.

28

8. The horseshoes

This is a subject about which I know very little, and throughout my enquiries about the Castle it has been the

subject that least aroused my interest. Having said that, I feel disposed nonetheless to make just three

observations. Firstly, I do not believe that Queen Elizabeth I ever visited Oakham nor that the ascription of a

29

large horseshoe to her is correct: she may never have come nearer to Oakham than Burghley House.

Secondly, over the doorway into the petty sessions room is a small horseshoe, to which is attached an amusing

little story.

25

Emmerson (1981) is in accord with JLB on this matter.

26 See J L Barber, The Wase Papers in the Bodleian Library, Rutland Record 6 (1986), 212-13.

27 This Roman masonry is now in Rutland County Museum.

28 See T H McK Clough, The Horseshoes of Oakham Castle (1999).

29

Indeed the horseshoe referred to is now thought most likely to have been put up by Edward IV in 1470 (Clough 1999, 8-10).

25