Researching Rutland

Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society. - All rights reserved

Registered Charity No 700273

Search

Book Review

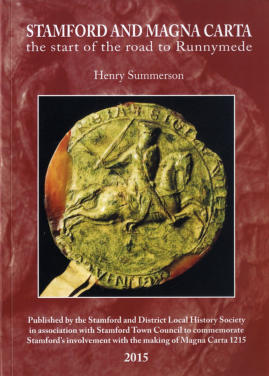

Stamford and Magna Carta: the start of the road to Runnymede

For the Stamford and District Local History Society in association with Stamford Town Council

Published by Abramis Academic Publishing in 2015 - Softbound – 60 pages – 150 x 210mm

Price £10 from local bookshops or via the Society website stamfordlocalhistorysociety.org.uk

At Easter 1215 a group of nobles, angered by King John’s taxation demands, assembled

at Stamford and marched south to challenge the king, sparking off a process which

culminated two months later on 15th June in the king’s reluctant acceptance of the

Magna Carta and the severe abridgement of royal rights which that represented. (The

gathering of the nobles is incorrectly dated on the back cover of the book).

That the sealing of Magna Carta was a matter of great historical significance cannot be

doubted. Just how significant it might have been continues to be much debated, not

least as a result of the major exhibition held recently at the British Library. This small but

informative volume does not concern itself with the wider significance of Magna Carta.

What it does do particularly well is to sketch the nature of the borough of Stamford in

the early years of the thirteenth century with a brief but clear exposition of its religious,

cultural and commercial importance at the time. This will prove extremely informative to

anyone interested in medieval Stamford and its hinterland, including Rutland.

Where the book is less successful is in establishing the links between the town and the

nobles who gathered there. Why the nobles should have gathered at Stamford is treated

speculatively. (It might, of course, be the case that the reason for the gathering at

Stamford cannot be definitively established). We can infer, of course, that this is a

reflection of Stamford’s importance, and Dr Summerson does assert that Stamford was

‘ideally placed for their assembly’. However, this doesn’t explain why Stamford was

chosen in preference to a number of other towns, especially as Stamford was a royal

borough held under the stewardship of Earl Warenne who remained loyal to the king.

Neither does Dr Summerson discuss the debate about the identity of the barons who assembled at Stamford. He quotes the

contemporary list given by Roger of Wendover, acknowledges its deficiencies, as demonstrated over fifty years ago by Sir James Holt,

but doesn’t attempt to correct the list. Moreover, he makes no attempt to incorporate the analysis of the rebel barons undertaken by

Professor Matthew Strickland on behalf of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), which seems odd in view of Dr

Summerson’s own pivotal role in the production of the ODNB’s medieval biographies. In the final analysis, therefore, this small work,

erudite though it might be on the importance of Stamford in the early thirteenth century, is ultimately rather unsatisfying in linking

the town to the epochal events of the late spring and early summer of 1215.

Mike Tillbrook

Researching Rutland

© Rutland Local History and Record Society

Registered Charity No 700273

Book Review

Stamford and Magna Carta: the start of the road to Runnymede

By Henry Summerson

Published by Abramis Academic Publishing in 2015

Softbound – 60 pages – 150 x 210mm Price £10 from

Stamfordlocalhistorysociety.org.uk

At Easter 1215 a group of nobles, angered by King John’s taxation

demands, assembled at Stamford and marched south to challenge the

king, sparking off a process which culminated two months later on

15th June in the king’s reluctant acceptance of the Magna Carta and the

severe abridgement of royal rights which that represented. (The gathering

of the nobles is incorrectly dated on the back cover of the book).

That the sealing of Magna Carta was a matter of great historical

significance cannot be doubted. Just how significant it might have been

continues to be much debated, not least as a result of the major exhibition

held recently at the British Library. This small but informative volume does

not concern itself with the wider significance of Magna Carta. What it does

do particularly well is to sketch the nature of the borough of Stamford in

the early years of the thirteenth century with a brief but clear exposition of

its religious, cultural and commercial importance at the time. This will

prove extremely informative to anyone interested in medieval Stamford

and its hinterland, including Rutland.

Where the book is less successful is in establishing the links between the

town and the nobles who gathered there. Why the nobles should have

gathered at Stamford is treated speculatively. (It might, of course, be the

case that the reason for the gathering at Stamford cannot be definitively

established). We can infer, of course, that this is a reflection of Stamford’s

importance, and Dr Summerson does assert that Stamford was ‘ideally

placed for their assembly’. However, this doesn’t explain why Stamford

was chosen in preference to a number of other towns, especially as

Stamford was a royal borough held under the stewardship of Earl

Warenne who remained loyal to the king.

Neither does Dr Summerson discuss the debate about the identity of the

barons who assembled at Stamford. He quotes the contemporary list

given by Roger of Wendover, acknowledges its deficiencies, as

demonstrated over fifty years ago by Sir James Holt, but doesn’t attempt

to correct the list. Moreover, he makes no attempt to incorporate the

analysis of the rebel barons undertaken by Professor Matthew Strickland

on behalf of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), which

seems odd in view of Dr Summerson’s own pivotal role in the production

of the ODNB’s medieval biographies. In the final analysis, therefore, this

small work, erudite though it might be on the importance of Stamford in

the early thirteenth century, is ultimately rather unsatisfying in linking the

town to the epochal events of the late spring and early summer of 1215.

Mike Tillbrook