Stukeley and Stamford, Part II, Tribulations of an Antiquarian Clergyman, 1730–1738

Edited by John F H Smith, 2023

152 pages. Hardback - ISBN 9781910653104

The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, Suffolk - (Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, Series Volume 111)

On

a

warm,

sunny

evening

in

June

2023,

I

had

the

pleasure

of

attending

Lincoln

Record

Society’s

formal

book

launch

for

both

volumes

of

its

Stukeley

and

Stamford

series,

held

in

the

elegant

surroundings

of

the

Court

Room

in

Stamford’s

Georgian

Town

Hall.

During

a

convivial

evening,

the

editors

of

both

volumes

gave

lively,

knowledgeable

talks

about

their

fascination

with

the

life

and

legacy

of

William

Stukeley

(1687–1765).

The

Lincolnshire

physician,

antiquarian

and

latterly

Anglican

clergyman

is

probably

best

remembered

as

the

father

of

British

archaeology

and

for

undertaking

the

first

rigorous

studies

of

the

Neolithic

stone

circles

at

Avebury,

Stanton

Drew

and

Stonehenge.

The

motivation

for

both

volumes

was

to

remedy

the

relative

neglect

of

Stukeley’s

years

in

Stamford

(1730–1748),

leading

the

editors

to

research

and

bring

to

the

public

eye

many

documents

that

had

not

been

touched

for

some

time,

including

an

anonymous,

handwritten

commentary

on

the

election

in

Stamford,

The

Historical

Part

of

Stamford

Election,

1734, which recent analysis has shown was written by Stukeley in the May of that year.

John

F

H

Smith

’s

volume,

the

second

in

the

Stukeley

and

Stamford

series,

is

a

beautiful,

large

format,

hardback

book

(32

cm

x

23.5

cm)

which

shares

the

same

elegant,

crisp

typeset

and

layout

as

the

first

volume.

The

large

format

allows

for

generous

reproductions

of

both

drawings

and

documents.

The

dust

cover

has

an

image

of

Stukeley’s

1736

sketch

of

Peter

Hill

and

the

castle

in

Stamford

viewed

from

the

south.

Inside,

there

are

another

62

illustrations,

32

in

colour,

including

many

of

Stukeley’s

drawings,

sketches,

paintings

and

maps.

There

are

also

full

colour

images

of

Savile

Cust’s

petition

to

Parliament

raising

his

grievances

following

the

1734

general

election

and

of

John

Proby’s

submission

to

Parliament

defending

his

election

as

one

of

the

two

MPs

for

Stamford.

The

depth

of

the

editor’s

research,

in

library

special

collections

or

private

collections,

is

evidenced

by

the

wealth

of

footnotes

which

themselves

provide

a

rich

source

of

contextual

and

explanatory

material

while

allowing

the

documents,

and

thereby

their authors, to speak for themselves.

The

time

period

in

Stukeley’s

life

considered

in

the

second

volume

overlaps

with

the

end

of

that

addressed

in

the

first

(Honeybone

and

Honeybone,

2021).

This

series

is

the

result

of

a

close

collaboration

between

the

editors

of

both

volumes

and

Smith

says

that

they

‘discussed

everything

in

detail

at

every

stage’

(p

x).

Consequently,

there

are

many

links

between

the

volumes.

Although

the

enjoyment

of

new

readers

to

this

series

does

not

depend

on

having

read

the

first

volume,

reading

(or

rereading)

Honeybone

and

Honeybone’s

introduction

to

Stukeley’s

character,

his

life

before

moving

to

Stamford,

and

the

full

versions

of

his

books

Iter

Oxoniense

(1710)

and

Stanfordia Illustrata (1736-7) in the first volume will only enrich readers’ enjoyment of the second.

Aside

from

the

appendices

and

biographies,

the

second

volume

can

be

divided

into

three

sections.

In

the

first,

Smith

sets

the

scene

by

narrating

Stukeley’s

life

from

his

application

to

be

ordained

to

the

mid-1740s.

Smith

considers

Stukeley’s

motivation

for

being

ordained

in

the

Church

of

England

and

his

hostile

reception

when

he

accepted

the

living

of

All

Saints’,

Stamford,

as

an

inexperienced

free-thinking,

Whig,

low

churchman

in

‘a

conservative

Tory

town

with

Jacobite

tendencies’

(p

3).

I

was

particularly

interested

in

the

background

to

the

1734

general

election

in

Stamford

and

the

account

of

how

the

agents

of

the

victorious

Tory

families,

particularly

the

Cecils

of

Burghley

and

the

Noels

of

Exton,

who

dominated

the

borough’s

corporation

and

its

parliamentary

representation,

as

Stukeley

puts

it,

‘set

their

revengeful

witts

[sic]

to

work’

on

him

in

response

to

his

high-profile

support

of

the

Whig

candidates,

especially

after

the

Riot

of

Friary

Gate,

by

means

of

a

‘barrage

of

lawsuits’

(p

9).

Another

strength

is

Smith’s

detailed

and

balanced

account

of

the

long-running

dispute

over

the

administration

of

Browne’s

hospital

in

Stamford,

which

caused

both

sides

to

lose

their

sense

of

proportion

and,

probably,

good

judgement,

and

which

further

soured

Stukeley’s

relationships

with

some

of

the

town’s

inhabitants,

leading

to

his

withdrawal

from

public

life in the late 1730s to concentrate on his parishes and completing writing-up of his discoveries at Stonehenge and Avebury.

In

passing,

historians

of

Rutland

will

note

the

account

of

two

families

with

large

landholdings

in

Rutland,

the

Cecils

of

Burghley

House

and

the

Noels

of

Exton,

uniting

to

ensure

the

borough

of

Stamford

returned

two

Tory

MPs

to

consolidate

Tory

dominance

over

the

town’s

political

life.

Both

candidates

for

the

confrater

of

Browne’s

hospital

in

1738

also

had

ties

to

Rutland:

the

Rev

Henry

Ridlington

was

from Edith Weston and William Ross was educated at Oakham School.

The

second

section

includes

Stukeley’s

account

of

the

1734

general

election

in

Stamford,

The

Historical

Part

of

Stamford

Election,

1734,

which

he

wrote

and

presented

to

Sir

Robert

Walpole

(regarded

as

Britain’s

first

Prime

Minister).

This

extraordinary

document

is

accompanied

by

an

introduction

and

footnotes

for

explanation

and

elucidation

as

well

as

the

full

texts

of

Savile

Cust’s

petition

to

the

House

of

Commons

Committee

of

Privileges

and

Elections

following

the

election

result

and

a

draft

of

John

Proby’s

submission

to

the

House

of

Commons

in

his

own

defence.

All

three

documents

are

remarkable

survivals

from

the

early

Georgian

period.

As

Smith

observes,

‘it

is

very

rare

for

detailed

written

accounts

of

the

events

leading

up

to

an

election,

and

the

election

itself,

to

survive,

especially

by

someone

deeply

involved

in

the

process…

Stukeley’s

record

is

unique

and

without

it

the

events

he

describes,

such

as

the

battle

at

Friary Gate, would be entirely unknown’ (pp 22-23).

Although

both

sides

would

have

interpreted

the

causes,

events

and

documents

in

radically

different

ways,

Smith

is

careful

to

afford

them

as

much

balance

as

possible

after

almost

three

centuries.

Smith

then

lets

Stukeley

make

his

case

in

his

own

distinctive

voice,

recounting

the

testimonies

of

Whig

inhabitants

of

Stamford

with

his

own

particular

perspective

on

the

actions

of

the

agents

of

Brownlow

Cecil,

8th

Earl

of

Exeter,

and

Baptist

Noel,

4th

Earl

of

Gainsborough,

over

the

year

prior

to

the

election.

Smith

provides

the

reader

with

detailed

footnotes

setting

out

the

context

and

corrections

where

Stukeley’s

account

is

exaggerated,

mistaken

or

omits

salient

points.

Although

allegations

of

bribery,

corruption

and

violence

were

frequently

made

by

both

Tories

and

Whigs

about

their

opponents’

conduct

during

eighteenth

century

elections,

the

1734

general

election

in

Stamford

appears

to

have

been

an

extreme

example.

There

cannot

be

many

other

recorded

instances

of

parliamentary

candidates

leading

a

mob

of

their

agents

and

supporters

heavily

armed

with

stones,

cudgels and, possibly, a few swords, to the home of one of their opponents as happened in the Riot of Friary Gate.

The

third

section

focuses

on

Stukeley’s

Designs

of

Stanford

Antiquitys,

Centuria,

I,

1735.

A

sketchbook

probably

intended

to

illustrate

another

of

his

works,

Stanfordia

Illustrata,

Stukeley’s

Designs

depicts

many

of

the

ancient

buildings,

monuments

and

landmarks

around

Stamford that Stukeley visited with his friend, the Rev William Warburton, and then recorded in Stanfordia Illustrata.

As

Smith

observes,

the

importance

of

Stukeley’s

Designs

lies

not

in

the

numerous

printed

plates,

many

by

another

of

Stukeley’s

friends

and

collaborators,

the

Rev

Francis

Peck,

but

in

Stukeley’s

own

sketches

of

‘buildings

and

features

that

no

longer

survive

[because]

his

drawings

are

the

sole

remaining

pictorial

evidence

of

their

existence’

(p

50).

Stukeley’s

ability

to

make

accurate,

objective,

closely

observed

records

was

recognised

by

contemporary

antiquarians

and

is

still

acknowledged

today.

It

was

these

skills

that

he

employed

so

effectively

at

Avebury

and

Stonehenge.

Stukeley’s

problem

was

that

many

of

the

ancient

buildings

that

he

drew

had

been

altered

significantly

or

demolished

before

he

took

up

residence

in

Stamford.

This

led

Stukeley

to

develop

a

critical

method

for

making

reconstructions

of

the

original

buildings

by

making

comparisons

with

extant

buildings,

folk

memory

and

the

memories

of

older

inhabitants,

which

Smith

describes.

One

of

the

highlights

is

a

reproduction

of

part

of

the

Knipe

map

of

Stamford

(1833),

fascinating

in

its

own

right,

annotated

with

sites

that

Stukeley

illustrated

in

his

Designs

from

speculations

about

the

foundation

of

Stamford

in

the

early

medieval

period

by

the

Saxon

leader

Hengist,

through

to

the

sites

of

Stamford’s

friaries

and

objective

records

of

existing

buildings

such

as

All

Saints’

vicarage

and

Sempringham

Hall.

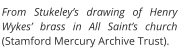

Another

two

highlights

are

Stukeley’s

drawings

of

the

monumental

brass

installed

in

All

Saints’

church

commemorating

one

of

his

predecessors,

Henry

Wykes

,

who

owned

the

manor

of

Burghley,

and

the

decorative

stone

panel

that

Stukeley

drew

in

situ

in

Sempringham

Hall’s

courtyard,

which

Stukeley

believed

had

been

dug

up

from

the

ruins

of

the

nearby

Augustinian friary (and which was rediscovered during work at a property on the High Street in the early 1980s).

Like

his

contemporaries,

Stukeley’s

interpretation

of

these

buildings,

monuments

and

landmarks

rested

on

and

was

constrained

by

the

writings

of

earlier

antiquarians

such

as

Anthony

Wood,

Brian

Twyne

and

John

Leland,

whose

accounts

of

medieval

academic

halls

in

Stamford

are

printed

in

full

in

an

appendix.

Consequently,

Smith

counsels

against

deprecating

Stukeley’s

work

because

he

concurred

with

antiquarians

of

his

own

generation

and

earlier

who

‘built

a

whole

edifice

of

halls

and

colleges

in

Stamford

that

was

based

on

little

more

than

conjecture

and

suppo-

sitions’.

Stukeley’s

drawings

are

‘unique

records

of medieval buildings in Stamford now long vanished’ (p 51).

In

conclusion,

as

befits

the

subject’s

life

as

a

polymath,

Smith’s

volume

has

broad

appeal,

especially

to

anyone

with

an

interest

in

Stukeley

and

his

time

in

Stamford,

the

1734

parliamentary

contest,

or

the

development

of

Stamford

and

its

medieval

and

early

modern

architecture,

much

of

it

now

lost.

The

volume

will

also

appeal

to

those

interested

in

drawing

links

and

making

comparisons

between

the

county

of

Rutland

and

the

neighbouring

borough

of

Stamford

as

well

as

those

interested

in

the

early

legal

and

parliamentary

career

of

William

Noel

(1695-1762),

one

of

Stamford’s

MPs

from

1722

to

1747.

(William

Noel,

son

of

the

4th

Baronet

of

Kirkby

Mallory

in

Leicestershire,

was

a

distant

cousin

of

Baptist

Noel,

4th

Earl

of

Gainsborough,

of

Exton

House,

sharing

a

direct

male

ancestor

in

the

sixteenth

century,

Andrew

Noel

of

Dalby

in

Leicestershire.)

Both

volumes

in

the

Stukeley

and

Stamford

series

have

pride

of

place

on

my

bookshelves,

well-thumbed

as

they

contain

a

wealth

of

fascinating

detail

that

I

keep

dipping

into.

Perhaps

they

won’t

be

the

last:

I

agree

with

Smith’s

observation

that

‘a

full

comprehensive

biography

of

Stukeley

is

badly

needed’

and,

I

would

argue,

long

overdue

in

order

to

set

Stukeley’s

experiences

and

achievements

across

his

eventful

life

of

77

years

in

the

context

of

a

dynamic,

often

overlooked,

period

in

British history.

Reference:

Honeybone, D. and Honeybone, M. (eds) (2021) Stukeley and Stamford, Part I, Cakes and Curiosity:

the Sociable Antiquarian, 1710-1737. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press (Publications of the Lincoln Record Society, 109).

Richard Hunt

Researching Rutland

Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society. - All rights reserved

Registered Charity No 700273

Book Review

Researching Rutland

© Rutland Local History and Record Society

Registered Charity No 700273

Book Review

William Browne’s Town: The Stamford Hall Book 1465-1492

Stamford Survey Group in association with Stamford Town Council and

Stamford Civic Trust

Stamford is fortunate to have a Hall Book, a record of the council minutes

of the town. Until now it has remained in the town’s archives only to be

seen by historians with an appointment. With this transcript Alan Rogers

has made the first part of the Hall Book accessible to all and we are given

the opportunity to step back in time and discover what life was really like

in the fifteenth century. Future volumes are planned which will continue

the story of Stamford’s town affairs.

The book gives a remarkable insight into the lives of townspeople in

medieval England covering the years from 1465, shortly after the town’s

incorporation, until 1489 just after the death of William Browne. William

Browne was a very rich and important Merchant of the Staple. He

controlled the affairs of the town during this period, serving as Alderman

on several occasions. His legacy to Stamford is All Saints’ Church and

Browne’s Hospital.

As today, rules and regulations governed the lives of townsfolk. The

minutes record laws forbidding Sunday trading and fines for leaving

horses tied up in the wrong places on market days – as the editor

comments, ‘There were parking penalties even in medieval Stamford’. We

also find that there were designated places for dunghills and times when

animals could be brought into town. From this book we learn how law

and order was enforced and the punishments meted out to wrongdoers.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the volume is the tremendous

number of different trades pursued in the town. The wardens strictly

controlled the craftsmen to ensure the quality of goods and there was a

diversity of rules governing the guilds and the pageant of Corpus Christi.

Alan Rogers has had close links with Stamford and readers will no doubt

be familiar with his books The Medieval Buildings of Stamford

(Nottingham 1970), The Book of Stamford (Buckingham 1983) and, with

JS Hartley, The Religious Foundations of Medieval Stamford

(Nottingham 1974). He has also been closely involved with local history in

Rutland, most recently in Uppingham, inspiring and encouraging local

historians to record aspects of the history of that town.

For this volume Professor Rogers has written an excellent introduction

including the insight he has gained about the role of William Browne in

making the transcript. He also adds useful comments throughout the

volume and there is an excellent index. It is a shame that the Editorial

Conventions are not at the front of the book and a glossary would have

been useful for those less familiar with the legal terms of the medieval

period. Do not however be deterred by the plain cover: inside it is a

fascinating record not just for people in Stamford but for anyone

interested in town life in the Middle Ages. It is a book to dip into, and read

aloud it comes to life. It certainly merits a place on the bookshelf of

anyone interested in history.

Jean Orpin