The Medieval Earthworks of Rutland

By Robert F Hartley

2nd edition (2023), A4, 133 pages, Paperback. ISBN 978-0-9548200-4-6

Leicestershire Fieldworkers. Monograph series, 5

Forty

years

after

the

publication

of

the

first

edition,

the

Leicestershire

Fieldworkers

held

the

launch

event

for

the

second

edition

of

Robert

F.

Hartley’s

seminal

work

on

The

Medieval

Earthworks

of

Rutland

at

Rutland

County

Museum

as

part

of

the

2023

Festival

of

Archaeology.

This

monograph

is

the

result

of

many

years

of

painstaking

survey

work

and

research.

The

author

has

revisited

sites,

redrawn

most

of

his

site

plans

and

elaborated

on

his

careful

interpretations

of

the

earthworks,

drawing

on

new

research

and,

occasionally,

including

new

earthworks

such

as

the

site

of

a

water

mill

and

pond

dam

in

Belton-in-Rutland

discovered

in

the

1990s.

Appropriately,

the

monograph

is

dedicated

to

Anthony

Squires

(1946–2021),

a

Loughborough

man

who

had

a

passion

for

natural

history

and

was

a

much

respected

landscape historian specialising in the ancient woodlands, deer parks and gardens of Leicestershire and Rutland.

The

talks

at

the

book

launch

were

engaging

and

knowledgeable.

‘Fred’

Hartley

worked

with

Tim

Clough

and

Peter

Liddle

for

many

years:

Tim

Clough

was

the

Curator

of

Rutland

County

Museum

and

Oakham

Castle

and

Peter

Liddle

was

the

Archaeological

Survey

Officer

at

the

Leicestershire

Museums

Service

and

later

Leicestershire’s

Keeper

of

Archaeology.

The

three

have

been

friends

for

more

than

40

years

and

the

warmth

of

this

friendship

enriched

the

anecdotes

Messrs

Clough

and

Liddle

recalled

about

working

with

Hartley:

Hartley’s

talent

for

surveying

historical

landscapes,

the

enjoyment

and

satisfaction

he

got

from

it

and

how

Hartley

would

‘disappear’

for

days

doing

fieldwork.

Hartley

spoke

engagingly

about

how

he

adapted

the

‘crosshead

survey’

method

so

that

he

could

work

solo,

and

the

process

of

drawing

his

site

plans.

He

revisited

his

original

work

of

1983

motivated

by

three

rising

threats

posed

to

Rutland’s

earthworks:

construction

to

meet

the

demand for new housing; high intensity, mechanised arable farming practices; and the expansion of quarrying in the county.

The

second

edition

of

Hartley’s

The

Medieval

Earthworks

of

Rutland

is

the

fifth

monograph

published

by

the

Leicestershire

Fieldworkers.

In

the

same

format

as

the

original,

this

A4,

paperback

monograph

shares

the

same

clear,

crisp

and

highly

readable

typeset

as

the

third

and

fourth

in

the

Leicester

Fieldworkers’

series

of

monographs.

The

front

cover

has

a

stylised

reproduction

of

the

plan

of

the

manor

of

Lyndon

which

was

prepared,

probably

in

1662,

by

the

astrologer,

astronomer

and

professional

land

surveyor,

Vincent

Wing,

the

uncle

of

the

philosopher

and

astronomer,

Tycho

Wing.

With

109

pages,

the

second

edition

is

almost

twice

the

length

of

the

first.

The

A4

format

allows

for

generous

reproductions

of

plans,

maps

and

photographs.

In

total,

the

monograph

contains

twice

as

many

original

site

plans

(more

than

80),

17

landscape

maps

and

five

colour

illustrations.

Apart

from

the

author’s

site

plans,

treasures

among

its

illustrations

include

an

aerial

photograph

looking

east

over

Brooke

and

‘Town

Park’

from

1986,

the

central

part

of

the

1768

Ketton

estate

map,

a

colour

reproduction

of

Vincent

Wing’s

plan

of

the

manor

of

Lyndon

and

a

reproduction

of

the

1687

map

of

the

Clipsham

cum

Membris

Lordship made by Wing’s nephew, John Wing.

After

a

much-expanded

introduction

including

a

more

detailed

glossary

describing

the

characteristics

of

the

different

types

of

earthworks

found

in

Rutland,

Hartley

presents

his

gazetteer

and

site

surveys,

organised

by

the

1885

boundaries

of

the

civil

parishes

introduced

by

the

1866

Poor

Law

Amendment

Act.

In

Rutland,

these

boundaries

were

largely

in

agreement

with

those

of

the

medieval

parishes, except around Oakham, and have remained largely unchanged.

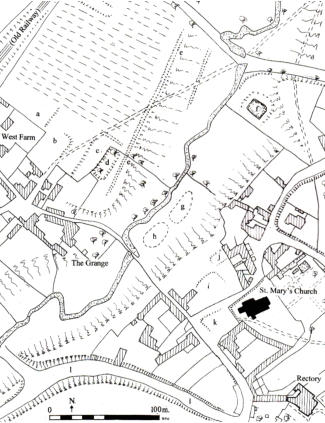

Hartley

’s

site

plans

are

full

of

fascinating

detail

for

the

reader

to

repeatedly

dip

into,

comprehensively

covering

Rutland’s

historic

landscape

and

features.

He

has

maintained

the

conventions

of

marking

parish

churches

in

solid

black

and

line

shading

other

buildings,

and

continues

the

tradition

of

making

accurate,

objective,

closely

observed

records

of

historical

landscapes

that

was

established

by

William

Stukeley

among

others.

Each

site

plan

is

accompanied

by

a

concise,

detailed

interpretation,

rich

in

references

to

other

works,

so

that

each

becomes

a

starting

point

for

those

who

wish

to

enrich

their

knowledge

of

the

site

and

its

context.

(The

new

edition

cites

45

works

in

contrast

to

the

13

books

referenced

in

the

first

edition.)

Although

I

moved

to

Rutland

more

than

ten

years

ago,

there

were

survey

sites

in

this

monograph

that

I

had

not

heard

of

before,

and

I

found

it

helpful

to

keep

to

hand

an

Ordnance

Survey

map

(there

are

map

references

for

each

site)

and

my

copy

of

An

Illustrated

Guide

to

the

Printed

Maps

of

Rutland

1576–1900

(Deadman

and

Brooks,

2012).

Although

readers’

enjoyment

does

not

depend

on

having

access

to

the

works

of

the

great

antiquarians

such

as

Thomas

Blore,

William

Stukeley

and

James

Wright,

reading

these

alongside

this

monograph

can

only enrich readers’ enjoyment, notably

Stukeley

’s Stanfordia Illustrata (1736–7).

In

conclusion,

I

would

recommend

the

second

edition

of

this

monograph

without

hesitation

to

anyone

who,

like

me,

is

fascinated

by

maps

or

interested

in

deepening

their

understanding

of

Rutland’s

landscape,

including

owners

of

the

first

edition.

It

will

also

be

an

essential

reference

for

landowners

on

whose

properties

these

earthworks

are

situated,

architects,

planning

officers

and

heritage

professionals

working

in

Rutland,

helping

them

to

understand

what

remains

of

individual

earthworks,

what

has

been

lost

and

their

wider

context.

Meantime,

the

monograph

has

wider

appeal

for

anyone

interested

in

Rutland’s

landscape

from

walkers

to

social

historians.

The

A4

format

will

appeal

to

walkers

interested

in

the

landscapes

they

are

walking

through,

and

the

monograph

will

fit

into

many

waterproof

map

cases.

Although

most

of

the

survey

sites

lie

on

private

property,

many

can

be

viewed

to

varying

degrees

from

Rutland’s

ancient

footpaths

and

bridleways

as

well

as

its

permissive

ways.

For

those

interested

in

the

social

history

of

Rutland,

Hartley’s

site

plans,

maps

and

interpretations

are

starting

points.

Study

of

this

guide

will

enable

the

inquiring

reader,

as

Tim

Clough

observes,

‘to

begin

to

populate

those

fields

and

their

strips

and

to

visualise

those

village

and

manor

sites’

(Hartley,

2023:

xiv),

further

brought

to

life

by

following

up

the

references

in

the

text

and

reading the works of the great antiquarians such as Thomas Blore, William Stukeley and James Wright.

Richard Hunt

References:

Deadman, D. and Brooks, C. (2012)

An Illustrated Guide to the Printed Maps of Rutland 1576–1900.

Leicester: The Landseer Press.

Hartley, R.F. (1983)

The Medieval Earthworks of Rutland.

1st edition. Leicester: Leicestershire Museums, Art Galleries and Records Service (Archaeological Reports Series, 7)

.

Hartley, R.F. (2023)

The Medieval Earthworks of Rutland.

2nd edition. Leicester: Leicestershire Fieldworkers (Monograph series, 5).

Researching Rutland

Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society. - All rights reserved

Registered Charity No 700273

Book Review

Researching Rutland

© Rutland Local History and Record Society

Registered Charity No 700273

Book Review

William Browne’s Town: The Stamford Hall Book 1465-1492

Stamford Survey Group in association with Stamford Town Council and

Stamford Civic Trust

Stamford is fortunate to have a Hall Book, a record of the council minutes

of the town. Until now it has remained in the town’s archives only to be

seen by historians with an appointment. With this transcript Alan Rogers

has made the first part of the Hall Book accessible to all and we are given

the opportunity to step back in time and discover what life was really like

in the fifteenth century. Future volumes are planned which will continue

the story of Stamford’s town affairs.

The book gives a remarkable insight into the lives of townspeople in

medieval England covering the years from 1465, shortly after the town’s

incorporation, until 1489 just after the death of William Browne. William

Browne was a very rich and important Merchant of the Staple. He

controlled the affairs of the town during this period, serving as Alderman

on several occasions. His legacy to Stamford is All Saints’ Church and

Browne’s Hospital.

As today, rules and regulations governed the lives of townsfolk. The

minutes record laws forbidding Sunday trading and fines for leaving

horses tied up in the wrong places on market days – as the editor

comments, ‘There were parking penalties even in medieval Stamford’. We

also find that there were designated places for dunghills and times when

animals could be brought into town. From this book we learn how law

and order was enforced and the punishments meted out to wrongdoers.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the volume is the tremendous

number of different trades pursued in the town. The wardens strictly

controlled the craftsmen to ensure the quality of goods and there was a

diversity of rules governing the guilds and the pageant of Corpus Christi.

Alan Rogers has had close links with Stamford and readers will no doubt

be familiar with his books The Medieval Buildings of Stamford

(Nottingham 1970), The Book of Stamford (Buckingham 1983) and, with

JS Hartley, The Religious Foundations of Medieval Stamford

(Nottingham 1974). He has also been closely involved with local history in

Rutland, most recently in Uppingham, inspiring and encouraging local

historians to record aspects of the history of that town.

For this volume Professor Rogers has written an excellent introduction

including the insight he has gained about the role of William Browne in

making the transcript. He also adds useful comments throughout the

volume and there is an excellent index. It is a shame that the Editorial

Conventions are not at the front of the book and a glossary would have

been useful for those less familiar with the legal terms of the medieval

period. Do not however be deterred by the plain cover: inside it is a

fascinating record not just for people in Stamford but for anyone

interested in town life in the Middle Ages. It is a book to dip into, and read

aloud it comes to life. It certainly merits a place on the bookshelf of

anyone interested in history.

Jean Orpin