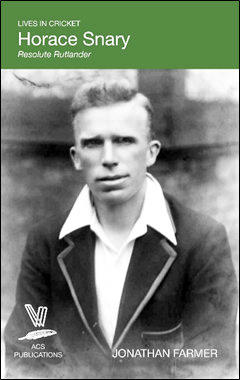

Horace Snary: Resolute Rutlander - Lives in Cricket No 59.

By Jonathan Farmer

Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians. ISBN: 978-1-912421-50-3. 240 pages - Available from jonathan.farmer17@gmail.com

Horace

Snary

has

earned

for

himself

a

footnote

in

the

history

of

English

county

cricket

as

the

most

economical

regular

bowler

the

County

Championship

has

produced,

conceding

an

average

of

only

1.72

runs

per

over

in

a

first-class

career

which

lasted

from

1921

to

1933.

However,

he

has

emerged

from

Jonathan

Farmer’s

meticulous

study

as

a

much

more

multi-faceted

character

than a mere recapitulation of his bowling analyses would imply.

Snary

and

his

twin

brother,

William,

were

born

in

Whissendine

in

1897.

At

the

time

of

Snary’s

birth

the

village

had

about

700

inhabitants,

most

of

whom

were

agricultural

labourers

who

were

often

struggling

to

maintain

their

standards

of

living

at

a

time

of

agricultural

depression.

It

was

still

a

rigidly

stratified

society

which

did,

however,

offer

a

range

of

social

activities,

with

many

of

which

the

Snary

family

were

connected.

However,

Snary’s

early

connections

with

cricket

seem

to

have

been

rather

rudimentary,

social

stratification

limiting

the

playing

opportunities

at

Whissendine

Cricket

Club

for

those

outside

the

ranks

of

the

gentry,

the

professions

and

the

more highly remunerated tradesmen.

Snary

was

sixteen

at

the

outbreak

of

the

Great

War,

but

by

the

beginning

of

1916

he

had

enlisted

in

the

2/6th

South

Staffordshire

Regiment.

He

originally

served

in

Ireland;

he

was

still

essentially

a

raw

recruit

in

the

early

days

of

the

Easter

Rising.

Promoted

to

Lance

Corporal

in

early

1917,

he

was

subsequently

promoted

to

the

rank

of

Sergeant,

a

significant

rise

through

the

ranks

for

a

young

village

boy,

who

must

be

presumed

to

have

developed

considerable

leadership

skills.

His

war

ended

prematurely

at

the

battle

of

Cambrai,

where

his

regiment

suffered

huge

casualties

in

the

defence

of

Bourlain

Wood

on

29/30

November

1917

and

he

himself

was

seriously

wounded.

In

common

with

many

veterans

of

the

Great

War,

Snary

was

reluctant

to

discuss

his

experiences;

neither

did

he

apply

to

receive

the

medals

to

which

he

was

entitled.

He

was

certainly

considerably

affected

by

the

death

of

his

twin

brother,

Willy,

and

these

factors

conceivably

led

him

to

be

suspicious

of

authority

and

might

have

contributed to his holding of political views which were somewhat at variance with received opinion in Rutland.

Snary

appears

not

to

have

played

cricket

in

1919.

In

any

case

he

was

still

recuperating

from

the

horrors

of

war.

However,

he

returned

to

the

game

in

1920.

By

this

time

the

social

stratification

which

had

underpinned

the

operation

of

Whissendine

Cricket

Club

was

breaking

down.

Moreover,

Snary

took

the

opportunities

to

develop

his

reputation,

to

the

extent

that

Leicestershire

offered

him

a

contract

for

1921.

Leicestershire

cricket

was

in

a

woeful

state;

no

fewer

than

34

players

represented

the

county

in

1921,

including

four

captains.

Snary

made

an

inauspicious

county

debut

in

that

year

–

against

Yorkshire

at

Headingley.

Wilfred

Rhodes

scored

267

not

out

and

Leicestershire

collapsed

ignominiously.

Snary’s

career

was

slow

to

take

off,

and

it

wasn’t

until

1926

that

he

became

established

in

the

side,

taking

33

wickets

in

9

matches

at

an

average

of

27.3.

He

appeared

regularly

thereafter

until

illness

and

injury

ended

his

first-class

career

in

1933.

His

best

season

was

1931,

during

which

he

took

101

wickets

at

an

average

of

18.11.

Perhaps

unfairly

pigeon-holed

as

a

defensive

bowler,

Snary

undoubtedly

suffered

from

being

the

reliably

accurate

bowler

in

what

had

become

a

rather

weak

side.

He

seems to have accepted his lot uncomplainingly and remained a committed team player.

Following

his

departure

from

the

first-class

game,

Snary

continued

to

play

leisure

cricket,

featuring

for

his

beloved

Whissendine

as

well

as

a

number

of

other

teams,

he

became

in

demand

because

of

his

skills

in

ground

maintenance

and

served

on

a

number

of

cricket

committees.

Unlike

many

of

his

contemporaries

from

the

cricket

field

he

had

prospered,

in

his

case

as

a

chicken

farmer,

and

thus

he

was

able

to

maintain

a

modestly

middle-class

living

standard.

All

of

this

is

skilfully

narrated

by

Jonathan

Farmer.

His

grasp

of

the

details

of

Snary’s

career

is

matched

by

meticulous

research

of

the

local

context.

He

has

no

doubt

that

Snary

was

a

‘praiseworthy

man’

who

‘by

virtue of his natural doggedness, overcame the odds to lead a full and rewarding life’.

Dr Mike Tillbrook

Researching Rutland

Copyright © Rutland Local History and Record Society. - All rights reserved

Registered Charity No 700273

Book Review

Researching Rutland

© Rutland Local History and Record Society

Registered Charity No 700273

Book Review

William Browne’s Town: The Stamford Hall Book 1465-1492

Stamford Survey Group in association with Stamford Town Council and

Stamford Civic Trust

Stamford is fortunate to have a Hall Book, a record of the council minutes

of the town. Until now it has remained in the town’s archives only to be

seen by historians with an appointment. With this transcript Alan Rogers

has made the first part of the Hall Book accessible to all and we are given

the opportunity to step back in time and discover what life was really like

in the fifteenth century. Future volumes are planned which will continue

the story of Stamford’s town affairs.

The book gives a remarkable insight into the lives of townspeople in

medieval England covering the years from 1465, shortly after the town’s

incorporation, until 1489 just after the death of William Browne. William

Browne was a very rich and important Merchant of the Staple. He

controlled the affairs of the town during this period, serving as Alderman

on several occasions. His legacy to Stamford is All Saints’ Church and

Browne’s Hospital.

As today, rules and regulations governed the lives of townsfolk. The

minutes record laws forbidding Sunday trading and fines for leaving

horses tied up in the wrong places on market days – as the editor

comments, ‘There were parking penalties even in medieval Stamford’. We

also find that there were designated places for dunghills and times when

animals could be brought into town. From this book we learn how law

and order was enforced and the punishments meted out to wrongdoers.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the volume is the tremendous

number of different trades pursued in the town. The wardens strictly

controlled the craftsmen to ensure the quality of goods and there was a

diversity of rules governing the guilds and the pageant of Corpus Christi.

Alan Rogers has had close links with Stamford and readers will no doubt

be familiar with his books The Medieval Buildings of Stamford

(Nottingham 1970), The Book of Stamford (Buckingham 1983) and, with

JS Hartley, The Religious Foundations of Medieval Stamford

(Nottingham 1974). He has also been closely involved with local history in

Rutland, most recently in Uppingham, inspiring and encouraging local

historians to record aspects of the history of that town.

For this volume Professor Rogers has written an excellent introduction

including the insight he has gained about the role of William Browne in

making the transcript. He also adds useful comments throughout the

volume and there is an excellent index. It is a shame that the Editorial

Conventions are not at the front of the book and a glossary would have

been useful for those less familiar with the legal terms of the medieval

period. Do not however be deterred by the plain cover: inside it is a

fascinating record not just for people in Stamford but for anyone

interested in town life in the Middle Ages. It is a book to dip into, and read

aloud it comes to life. It certainly merits a place on the bookshelf of

anyone interested in history.

Jean Orpin